|

A treasure trove is an amount of money or coin, gold, silver, plate, or bullion found hidden underground or in places such as cellars or attics, where the treasure seems old enough for it to be presumed that the true owner is dead and the heirs undiscoverable. An archaeological find of treasure trove is known as a hoard. The legal definition of what constitutes treasure trove and its treatment under law vary considerably from country to country, and from era to era.

Treasure trove, literally means "treasure that has been found". The English term treasure trove was derived from tresor trové, the Anglo-French equivalent of the Latin legal term thesaurus inventus. In 15th-century English the Anglo-French term was translated as "treasure found", but from the 16th century it began appearing in its modern form with the French word trové anglicized as trovey, trouve or trove. The term wealth deposit has been proposed as a more accurate alternative.

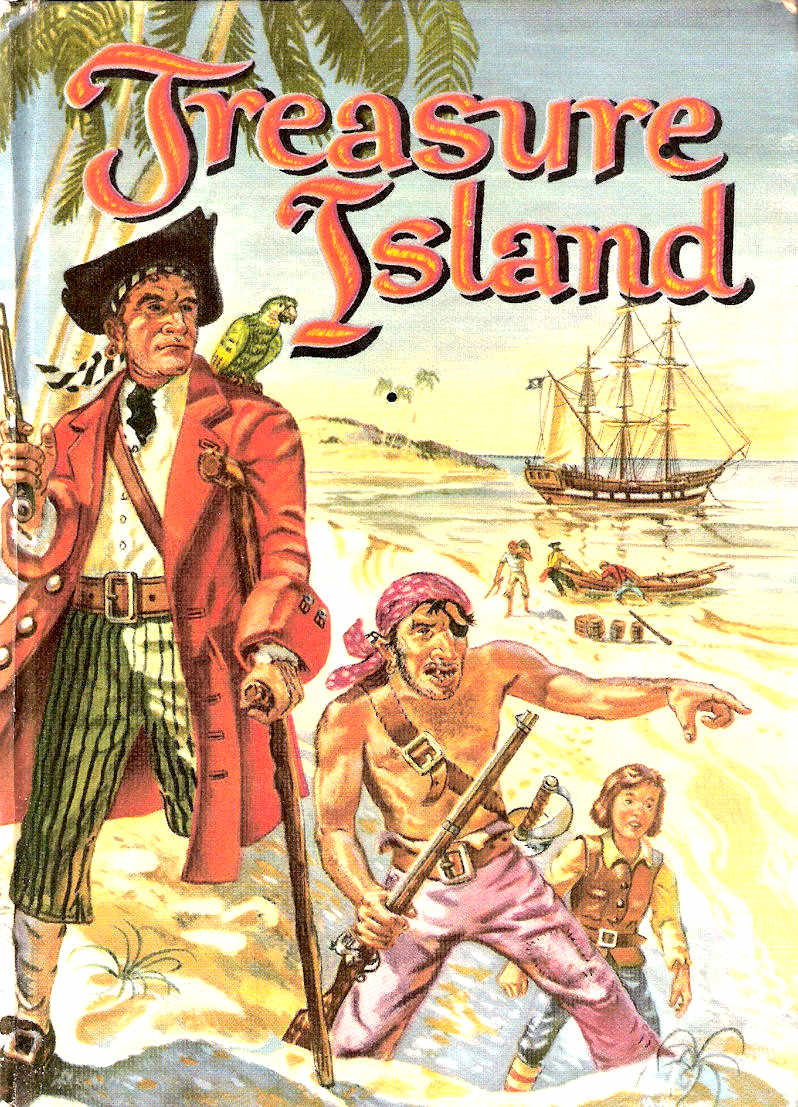

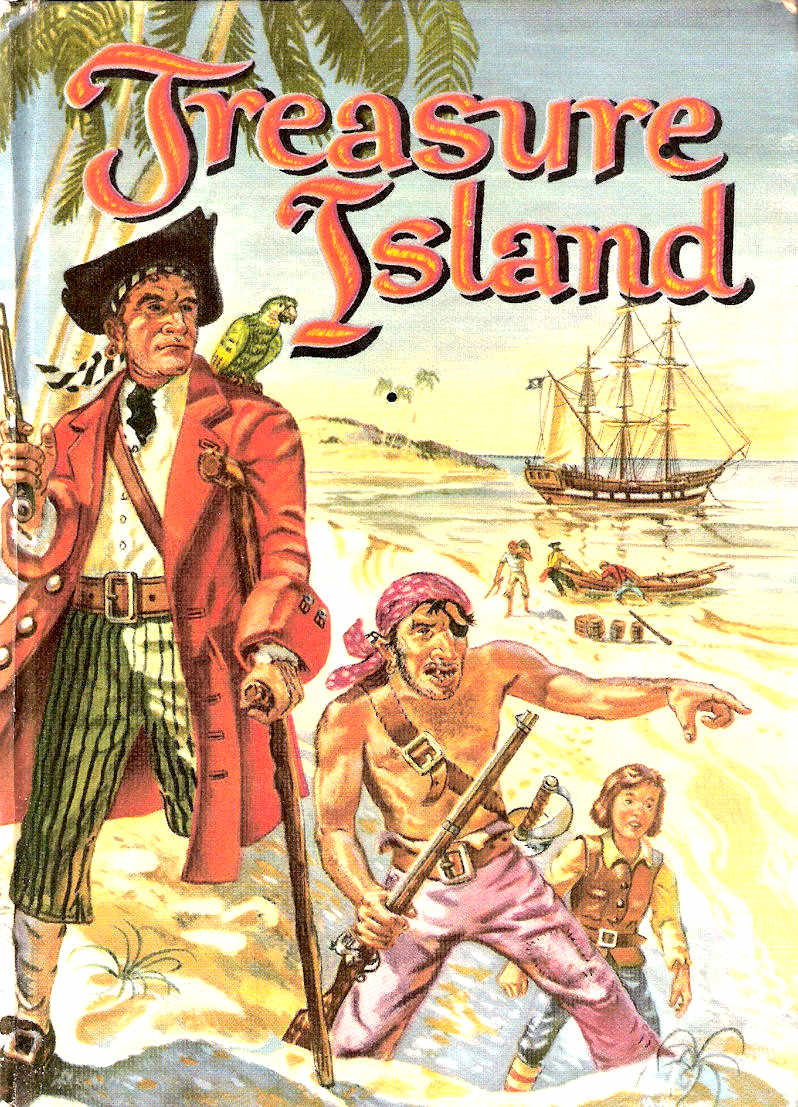

PIRATES

TREASURE

Pirates

who bury their loot, come into a different category. By definition the goods

were not theirs in the first place. They were robbed or stolen, typically on

the high seas, some with licence to do so from Kings and Queens. Being

silver, gold and gemstones, barter was involved. Also, pirates would not

give up treasure for a very small percentage reward, because they are not

law abiding citizens. They don't like paying taxes, choosing instead a life

on the high seas.

A

buried hoard is a sort of bank. Unlike euros, dollars, or pounds, the

treasure is not in paper currency, that can go up and down in value. Pirates

treasure, remains at the going rate for the precious metal, as do diamonds.

Normally, gold outperforms the rate of inflation several times over. So is a

good investment. Unlike pensions and savings in the modern world, that

typically reduce in value as governments foul up the economy. It makes us

wonder why we all don't go back to gold coins - the gold standard. They

would not have to be minted from any nation. They could just be a set

weight. Ten, twenty or 50 gram gold coins. And the same in silver for lower

value purchases.

Alternatively,

we could trade in agricultural

produce. And have an agricultural $dollar. Or energy, and have a

methanol £pound or kilowatt €euro. That way we might not superheat the

economy. Stopping governments from spending and borrowing more than the

planet can afford. The beginnings of a true Circular

Economy.

Then

eventually, as the pirates aged, there would have to look at retirement. For

most this would mean purchasing a farm estate, and converting their treasure

into land. Captain Henry Morgan did just that, living off the legitimate

produce from his plantations. Apart from using slaves. A practice that has

now been abolished in most countries. Except for financial slavery. Making

banks modern fiscal pirates, or slave traders.

Today,

governments would be strongly opposed to any form of currency that they

could not track and tax, tax, tax. Mostly, to fund their corrupt

administrations, consultancy payments on the side, and procurement fraud.

But there is a legitimate reason for tracking international money transfers,

and that is to detect terrorism and prevent drug money from being laundered.

Why

then don't the terrorists and drug cartels trade using gold bullion? Or

legitimate medicines.

ENGLISH COMMON LAW

Under the common law, treasure trove was defined as gold or silver in any form, whether coin, plate (gold or silver vessels or utensils) or bullion (a lump of gold or silver), which had been hidden and rediscovered, and which no person could prove he or she owned. If the person who had hidden the treasure was known or discovered later, it belonged to him or her or persons claiming through him or her such as descendants. To be treasure trove, an object had to be substantially – that is, more than 50% – gold or silver.

Treasure trove had to be hidden with animus revocandi, that is, an intention to recover it later. If an object was simply lost or abandoned (for instance, scattered on the surface of the earth or in the sea), it belonged either to the first person who found it or to the landowner according to the law of finders, that is, legal principles concerning the finding of objects. For this reason, the objects found in 1939 at Sutton Hoo were determined not to be treasure trove; as the objects were part of a ship burial, there had been no intention to recover the buried objects later. The Crown had a prerogative right to treasure trove, and if the circumstances under which an object was found raised a prima facie presumption that it had been hidden, it belonged to the Crown unless someone else could show a better title to it. The Crown could grant its right to treasure trove to any person in the form of a franchise.

It was the duty of the finder, and indeed of anyone who had acquired knowledge of the matter, to report the finding of a potential treasure trove to the coroner of the district. Concealing a find was a misdemeanour punishable with fine and imprisonment. The coroner was required to hold an inquest with a jury to determine who were the finders or the persons suspected to be the finders,

"and that may be well perceived where one liveth riotously and have done so of long

time". Where there had been an apparent concealment of treasure trove the coroner's jury could investigate the title of the treasure to discover if it had been concealed from the supposed owner, but any such finding was not conclusive as the coroner generally had no jurisdiction to enquire into questions of title to the treasure between the Crown and any other claimant. If a person wished to assert title to the treasure, he or she had to bring separate court proceedings.

In the early 20th century, it became the practice of the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury to pay those finders who fully and promptly reported discoveries of treasure troves and handed them over to the proper authorities, the full antiquarian value of objects which were retained for national or other institutions such as museums. Objects not retained were returned to the finders.

The law regarding treasure trove was amended in 1996 so that these principles no longer apply.

TREASURE ACT 1996 (UK)

Throughout the ages, farmers, archaeologists and amateur treasure hunters have unearthed important treasures of immense historical, scientific and financial value. However, the strictness of the common law rules meant that such items were sometimes not treasure trove. The items risked being sold abroad, or were only saved for the nation by being purchased at a high price. Mention has already been made of the objects comprising the Sutton Hoo ship burial, which were not treasure trove as they had been interred without any intention to retrieve them. The objects were later presented to the nation by their owner, Edith May Pretty, in a 1942 bequest. In March 1973, a hoard of about 7,811 Roman coins was found buried in a field at Coleby in Lincolnshire. It was made up of antoniniani believed to have been minted between AD 253 and 281. The Court of Appeal of England and Wales held in the 1981 case of Attorney-General of the Duchy of Lancaster v. G.E. Overton (Farms) Ltd. that the hoard was not treasure trove as the coins were bronze and did not have a substantial silver content. Thus, it belonged to the owner of the field and could not be retained by the British Museum.

To remedy the faults of the old treasure trove regime, the Treasure Act 1996 introduced a new scheme which came into effect on 24 September 1997. Any treasure found on and after that date regardless of the circumstances in which it was deposited, even if it was lost or left with no intention of recovery, belongs to the Crown, subject to any prior interests or rights held by any franchisee of the Crown. The Secretary of State (currently meaning the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport) may direct that any such treasure be transferred or disposed of, or that the Crown's title in it be disclaimed.

The Act uses the term treasure instead of treasure trove; the latter term is now confined to objects found before the Act came into force.

When treasure has vested in the Crown and is to be transferred to a museum, the Secretary of State is required to determine whether a reward should be paid by the museum before the transfer to the finder or any other person involved in the finding of the treasure, the occupier of the land at the time of the find, or any person who had an interest in the land at the time of the find or has had such an interest at any time since then. If the Secretary of State determines that a reward should be paid, he or she must also determine the market value of the treasure (assisted by the Treasure Valuation Committee), the amount of the reward (which cannot exceed the market value), to whom the reward should be paid and, if more than one person should be paid, how much each person should receive.

UNITED STATES

Many states in the U.S. enacted statutes that received English common law into their legal systems. For example, in 1863 the legislature of Idaho enacted a statute that made "the common law of England ... the rule of decision in all courts" of the state. However, English common law principles of treasure trove were not applied in the U.S. Instead, courts applied rules relating to the finding of lost and ownerless items. The treasure trove rule was first given serious consideration by the Oregon Supreme Court in 1904 in a case involving boys who had discovered thousands of dollars in gold coins hidden in metal cans while cleaning out a henhouse. The Court wrongly believed that the rule operated in the same way as early rules that awarded possession – and, effectively, legal title as well – to innocent finders of items that had been hidden or concealed and the owners of which were unknown. By awarding the coins to the boys, the Court implied that finders were entitled to buried valuables, and that any claims by landowners should be disregarded.

In subsequent years the legal position became unclear as a series of English and American cases decided that landowners were entitled to buried valuables. The Maine Supreme Judicial Court reconsidered the rule in 1908. The case before it involved three workers who had found coins while digging on their employer's land. The Court decided along the lines of the 1904 Oregon case and awarded the coins to the finders. For the next 30 years, the courts of a number of states, including Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Ohio and Wisconsin, applied this modified "treasure trove" rule, most recently in 1948. Since that time, however, the rule has fallen out of favour. Modern legal texts regard it as "a recognized, if not controlling, rule of decision", but one commentator has called it "a minority rule of dubious heritage that was misunderstood and misapplied in a few states between 1904 and 1948".

STATE LAWS

The law of treasure trove in the United States varies from state to state, but certain general conclusions may be drawn. To be treasure trove, an object must be of gold or silver. Paper money is also deemed to be treasure trove since it previously represented gold or silver. On the same reasoning, it might be imagined that coins and tokens in metals other than gold or silver are also included, but this has yet to be clearly established. The object must have been concealed for long enough so it is unlikely that the true owner will reappear to claim it. The consensus appears to be that the object must be at least a few decades old.

A majority of state courts, including those of Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, New York, Ohio, Oregon and Wisconsin, have ruled that the finder of treasure trove is entitled to it. The theory is that the English monarch's claim to treasure trove was based on a statutory enactment which replaced the finder's original right. When this statute was not re-enacted in the United States after its independence, the right to treasure trove reverted to the finder.

In Idaho and Tennessee courts have decided that treasure trove belongs to the owner of the place where it was found, the rationale being to avoid rewarding trespassers. In one Pennsylvania case, a lower court ruled that the common law did not vest treasure trove in the finder but in the sovereign, and awarded a find of US$92,800 cash to the state. However, this judgment was reversed by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania on the basis that it had not yet been decided if the law of treasure trove was part of Pennsylvania law. The Supreme Court deliberately refrained from deciding the issue.

Finds of money and lost property are dealt with by other states through legislation. These statutes usually require finders to report their finds to the police and transfer to their custody the objects. The police then advertise the finds to try to locate their true owner. If the objects remain unclaimed for a specified period of time, title in them vests in the finders. New Jersey vests buried or hidden property in the landowner, Indiana in the county, Vermont in the town, and Maine in the township and the finder equally. In Louisiana, French codes have been followed, so half of a found object goes to the finder and the other half to the landowner. The position in Puerto Rico, the laws of which are based on civil law, is similar.

Finders who are trespassers generally lose all their rights to finds, unless the trespass is regarded as "technical or trivial".

Where the finder is an employee, most cases hold that the find should be awarded to the employer if it has a heightened legal obligation to take care of its customers' property, otherwise it should go to the employee. A find occurring in a bank is generally awarded to the bank as the owner is likely to have been a bank customer and the bank has a fiduciary duty to try to reunite lost property with their

owners. For similar reasons, common carriers are preferred to passengers and hotels to guests (but only where finds occur in guest rooms, not common areas). The view has been taken that such a rule is suitable for recently misplaced objects as it provides the best chance for them to be reunited with their owners. However, it effectively delivers title of old artefacts to landowners, since the older an object is, the less likely it is that the original depositor will return to claim it. The rule is therefore of little or no relevance to objects of archaeological value.

Due to the potential for a conflict of interest, police officers and other persons working in law enforcement occupations, and armed forces are not entitled to finds in some states.

FEDERAL LAW

U.S. Federal laws governing recovery of treasure are governed by the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979, Under ARPA, "archaeological resources" more than one hundred years old on public lands belong to the government. The term "archaeological resource" means any material remains of past human life or activities which are "of archaeological interest", as determined by federal regulations. Such regulations include, but are not limited to: pottery, basketry, bottles, weapons, weapon projectiles, tools, structures or portions of structures, pit houses, rock paintings, rock carvings, intaglios, graves, human skeletal materials, or any portion or piece of any of the foregoing items.

The definition of "archaeological resource" and "archaeological interest" has been broadly interpreted under U.S. agency regulations in recent years to include nearly anything of human origin more than 100 years old, while permits to allow recovery of such items have been largely restricted to digs by credentialed archaeologists. The effect of ARPA as currently defined by federal regulations outlaws virtually all treasure hunting of items more than 100 years old, even treasure troves of gold and silver coin or scrip, under penalty of total forfeiture. Furthermore, the Federal policy against spoliation and removal of "archaeological resources" of any type from federal or Indian lands, even coins and scrip less than 100 years old, means it is unlikely that a finder of gold or silver coinage on Federal lands will prevail with an argument that the find constitutes a treasure trove of coinage, but rather "embedded property" that belongs to the property owner, i.e. the government.

The broad use of ARPA to target not only archaeological looting but also to prohibit all treasure hunting on federal or Indian lands has been criticized on the grounds that total prohibition and forfeiture simply encourages concealment or misrepresentation of the age of the found coinage or treasure trove, thus hampering archaeological research, as archaeologists cannot study items that when found will never be reported.

HOARDS

A hoard or "wealth deposit" is an archaeological term for a collection of valuable objects or artifacts, sometimes purposely buried in the ground, in which case it is sometimes also known as a cache. This would usually be with the intention of later recovery by the hoarder; hoarders sometimes died or were unable to return for other reasons (forgetfulness or physical displacement from its location) before retrieving the hoard, and these surviving hoards might then be uncovered much later by metal detector hobbyists, members of the public, and archaeologists.

Hoards provide a useful method of providing dates for artifacts through association as they can usually be assumed to be contemporary (or at least assembled during a decade or two), and therefore used in creating chronologies. Hoards can also be considered an indicator of the relative degree of unrest in ancient societies. Thus conditions in 5th and 6th century Britain spurred the burial of hoards, of which the most famous are the Hoxne Hoard, Suffolk; the Mildenhall Treasure, the Fishpool Hoard, Nottinghamshire, the Water Newton hoard, Cambridgeshire, and the Cuerdale Hoard, Lancashire, all preserved in the British Museum.

Prudence Harper of the Metropolitan Museum of Art voiced some practical reservations about hoards at the time of the Soviet exhibition of Scythian gold in New York City in 1975. Writing of the so-called "Maikop treasure" (acquired from three separate sources by three museums early in the twentieth century, the Berliner Museen, the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, and the Metropolitan Museum, New York), Harper warned:

"By the time "hoards" or "treasures" reach museums from the antiquities market, it often happens that miscellaneous objects varying in date and style have become attached to the original group."

Such "dealer's hoards" can be highly misleading, but better understanding of archaeology amongst collectors, museums and the general public is gradually making them less common and more easily identified.

SHIPWRECKS

AND THE LAW

Any item washed ashore from a ship, whether wrecked or not, constitutes ‘wreck’ under the law. Such goods belong to whoever had title to them before they fell into the sea. Where the goods are washed up as the result of a shipwreck, they must be declared to the receiver of the wreck, by the person finding them, within 28 days. The receiver may subsequently pass them back to the finder (if the owner cannot be found). Otherwise, a payment for the salvage of the goods may be payable by the receiver to the finder.

The failure of treasure

hunters to report items of wreck found is a criminal offence and the retention of goods ‘unofficially salvaged’ could lead to a prosecution for theft.

BLACK SWAN

The largest monetary treasure haul found was on the wreck code named Black Swan, discovered by Odyssey Marine Exploration in 2007 off of Gibraltar. The salvage team reportedly found 17 tons of coins valued at $500 million; an amount that is both staggering and said to be “unprecedented” in the treasure hunting world.

SS CITY OF CAIRO

A treasure that was thought to be forever lost has now seen the light of day after £50 million of cargo, namely silver rupee coins, was recovered from the British steam ship SS City of Cairo by Deep Ocean Search, in April 2015.

1715 SPANISH TREASURE FLEET

On July 31, 1715, a Spanish fleet of 11 ships loaded with treasure sailed into a hurricane and sank off the coast of Florida (you may remember this story from the 2008 Matthew

McConaughey/Kate Hudson movie Fool’s Gold, which was based on the treasure).

More than $1 million worth of gold artefacts, including a rare coin destined for the King of Spain, were discovered in the shallow waters approximately 30 miles north of West Palm Beach. A family of professional treasure hunters, called the Schmitts, made the find in 2015.

The treasures were found among the 1715 Treasure Fleet, which sank as the result of a hurricane after leaving Havana, Cuba almost exactly 300 years ago. The artefacts, which were only about 15 feet deep in the water, included 51 gold coins and 40 feet of ornate gold chain.

Since then, coins have been washing up all along Florida’s “Treasure Coast.” Major hauls are still raking in the dough, including the $4.5 million cache that was found on the same day of the wreck 300 years later in shallow water just feet from shore.

Brent Brisben, owner of the 1715 Fleet as 'Queen's Jewels, LLC,' is quoted as saying:

"These finds are important not just for their monetary value, but their historical importance." "One of our key goals is to help learn from and preserve history, and this week's finds draw us closer to those truths."

Since the ship was recovered more than fifty years ago, divers have discovered about $50 million worth of treasure and it is thought more than $400 million worth of treasure may still be hiding below the sea. Please note that 'Queens Jewels LLC' owns the salvaging rights to the entire fleet.

OTHER SHIPS WAITING IN THE WINGS

It’s estimated there are around three million undiscovered shipwrecks around the world. Some are being searched for right now – and a few of those might even contain riches.

THE MERCHANT ROYAL

In 1641, the Merchant Royal sank off the coast of Cornwall due to bad weather. Although the anchor was discovered in 2019, the main shipwreck has never been discovered. At the time the ship went down, it was estimated to be carrying 100,000 pounds of gold. In today’s money, you can expect the cargo to be worth about £1bn.

THE SANTA MARIA

The Santa Maria was one of the ships which sailed with Christopher Columbus’ fleet on his way to – what is now – America. Although all arrived in port, the Santa Maria eventually set off on a search for valuables such as gold and spices.

According to the story, on Christmas Eve 1492, the cabin boy was put in charge of steering the ship. We can only assume the helmsman was celebrating the occasion. As you might have guessed, the Santa Maria ran aground on Haiti – resulting in the vessel being abandoned. Consequently, no-one knows the current location of the ship or its cargo.

THE FLOR DE LA MAR

A large Portuguese vessel, the Flor de la Mar made multiple trips across the Indian Ocean. However, after spending almost a decade sailing from one destination to the other, the vessel needed repairs. In the early 1500s, the ship was sent to reinforce a Portuguese campaign – despite being deemed unsafe at the time.

Perhaps not too surprisingly, the ship sank after being caught in a storm. Reportedly though, she went down with about £2bn worth of treasure on board.

LAS CINCO CHAGAS

Las Cinco Chagas sank in 1594 after a conflict with British privateers. Going down near Portugal, the ship was returning home following an expedition to India – reportedly carrying precious stones and diamonds.

The cargo is currently estimated to be worth more than half a billion pounds.

THE SAN JOSÉ

Called the “holy grail of shipwrecks,” the Spanish galleon San José was carrying a treasure of silver, gold, and emeralds worth billions of dollars today. The galleon sunk after a battle with British ships off the coast of Cartagena, Colombia, in 1708.

|