|

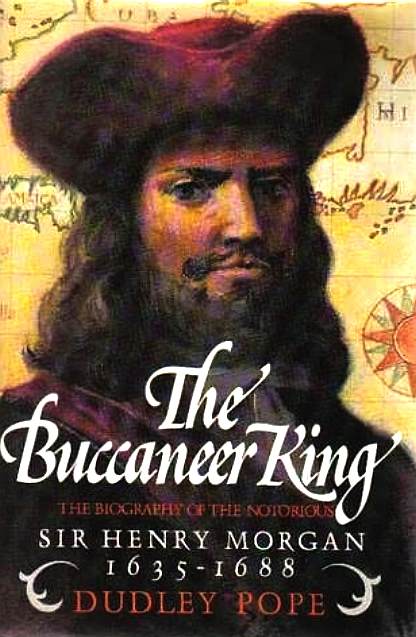

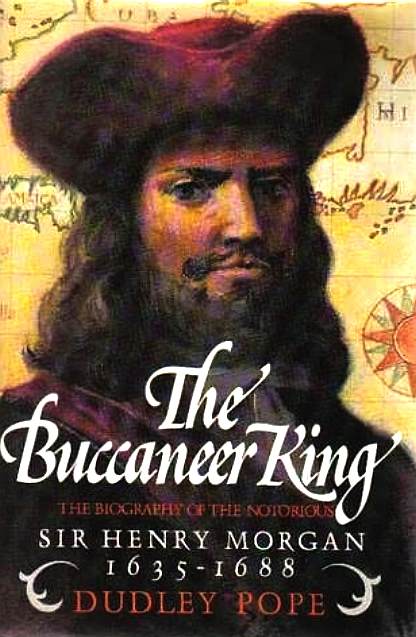

Sir

Henry Morgan, was a brilliant tactician and piratical businessman, able to

command the loyalty of privateers, who followed him into battle.

PIRATES OF THE PANAMA CANAL - HENRY MORGAN'S SATISFACTION

Long before the completion of the Panama

canal in 1914, this narrow stretch of the isthmus separating the Atlantic

and Pacific

oceans

(with the Caribbean

Sea in betwixt) was already used to avoid an 8,000-mile detour around Cape

Horn. Ships unloaded cargo at the mouth of the Chagres River, seven miles from the modern canal entrance. Flat-bottomed river barges then moved people and cargo upriver to within 13 miles of Panama City, where donkeys took over on the Camino de Cruces trail. “For four centuries the Chagres has been the bond of union between the two great oceans of the world, the way between the East and West,” wrote C.L.G. Anderson, an early-twentieth-century historian. Until the river became part of the canal it

inspired - dammed to form Gatun Lake - it was the original, natural “Panama

Canal,” and free to navigate.

Fort San Lorenzo sits on a promontory at the mouth of the Chagres River on Panama’s Caribbean coast. In 1671, the fleet of privateer

Henry Morgan attacked it on the way to sack Panama City. Archaeologists are searching Lajas Reef, under the surf 200 yards offshore, where five of Morgan’s ships sank, for insight into pirate life.

Like an illuminated skyline at sea, two dozen cargo ships wait along Panama’s Caribbean coast. One after another, they enter Limon Bay and then the Gatun locks, three hydraulic chambers that lift the ships 85 feet above sea level. They exit into Gatun Lake and then the Chagres River. After 28 miles, through a cleaved mountain ridge and under the Pan-American Highway, the ships enter more

locks - the Pedro Miguel lock and the two Miraflores locks - that ease the ships back down to sea level in Balboa Harbor, just southwest of

Panama City. A trip through the Panama Canal from Atlantic to Pacific takes around nine hours and costs tens of thousands of dollars in tolls.

Long before the completion of the canal in 1914, this narrowest stretch of the isthmus separating the oceans was already used to avoid an 8,000-mile detour around Cape Horn. Ships unloaded cargo at the mouth of the Chagres River, seven miles from the modern canal entrance. Flat-bottomed river barges then moved people and cargo upriver to within 13 miles of Panama City, where donkeys took over on the Camino de Cruces trail. “For four centuries the Chagres has been the bond of union between the two great oceans of the world, the way between the East and West,” wrote C.L.G. Anderson, an early-twentieth-century historian. Until the river became part of the canal it

inspired - dammed to form Gatun Lake - it was the original, natural “Panama Canal.”

Beginning in the sixteenth century, the Spanish used this route to supply Panama City and move gold and silver from the city to galleons in the Caribbean. In 1671, famed English privateer

Captain

Sir Henry Morgan took the largest pirate fleet in history up the river to sack the city and rattle Spain’s control of the Americas. And centuries later, during the California Gold Rush, it was easier for prospectors to take a steamer to Panama, sail up the river, then make their way north in the Pacific than it was to travel overland between America’s coasts. For all the precious metals that have traveled up and down it, the Chagres has been called “the world’s most valuable river.”

Since the first trans-isthmus railroad opened in 1855, the mouth of the Chagres River has been a backwater surrounded by a clotted jungle full of anteaters, toucans, and bellowing howler monkeys. On a promontory above, shaped like the prow of a massive ship, sit the ruins of El Castillo de San Lorenzo el Real de Chagre, or Fort San Lorenzo, which defended the important trade route between 1626 and 1741. It was sacked several times, including by Morgan’s men on their way to Panama City in 1671. Fritz Hanselmann, an underwater archaeologist at Texas State University, is looking for evidence of the privateer’s Panamanian

raid - but not in the fort. He’s focused on a string of whitecaps in the sea 200 yards from it, treacherous Lajas Reef, which sank five of Morgan’s ships, including his flagship Satisfaction.

Fritz Hanselmann’s work (Texas State University Underwater Archaeologist) is part of the Rio Chagres Maritime Landscape Study, which he started in 2008 with James Delgado of the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration, then director of the Institute of Nautical Archaeology at Texas A&M University. The nonprofit Waitt Institute was going to have a ship in the area to provide support, so Hanselmann and Delgado began a series of survey dives that January. They observed artifacts spanning 500 years, from sixteenth-century Spanish pottery to Gold Rush–era plates to modern military items. “There’s just all kinds of artifacts and material culture littering the seafloor and the mouth of the riverbed right by the fort,” Hanselmann

is quoted as saying.

On the second survey dive, the team found some unmistakable items -

encrusted with sea life, but still recognizable—in the rubble at the base of the reef. “There’s no confusing what it is,” says Delgado. “It’s not a sewer pipe. It’s a gun.”

More specifically, they were cannons, eight of them, in a variety of sizes. Nearby were three clusters of magnetic anomalies, suggesting to Hanselmann and Delgado that they had found remains of the only ships documented to have sunk on the

reef - Morgan’s. There was also clear evidence that artifact collectors had been there before: cut marks, drill holes, even craters from explosives. Because the cannons were at risk from looting or being lost in a storm, Panama’s National Institute of Culture (INAC) agreed they should be raised. Hanselmann returned to the site, with Waitt Institute funding, in 2010, to remove the cannons for study before continuing with the rest of the project. “It was largely go in, get the guns, get out,” says Hanselmann.

He and his team placed straps around each cannon (ranging from approximately 200 to 900 pounds), partially inflated lift bags, moved the cannons off the reef, and then towed them by boat to a nearby boat launch, where they used a piece of sailboat decking to slide them out of the water. Hanselmann calls it their “cost-effective cannon recovery system.” Only six were

recovered - the other two, the smallest ones, may have been moved by a storm. INAC did not have the facilities to store or treat the cannons. The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute then agreed to keep them for almost a year, until a private preservation group based in Panama City, Patronato Panamá Viejo, could outfit their conservation lab to study them. They prepared the cannons for display in a museum next to the ruins of the original Spanish Panama

City - the very one sacked by Morgan. If confirmed to be his, the cannons will be the only documented archaeological evidence of the pirate raid.

Captain Henry Morgan was the premier buccaneer of his age, the man who ransomed Portobello, Panama, and the man who used his own flagship as a decoy and feinted a landward attack to sneak out of heavily defended Maracaibo Harbor in Venezuela. “The name Morgan was really legend in the Caribbean,” says Stephan Talty, author of Empire of

Blue Water, about Morgan’s career. His modern

image - drawn largely from rum bottles - depicts a dashing, anarchic gadabout, but Morgan was more strategist than swashbuckler. He was also a patriot, from a good military family, who operated as a

privateer, a pirate licensed by the British Crown

(Queen

Anne, King

Charles II and King

James II) to steal from other countries’ ships and settlements -

especially Spain’s. “Morgan was sort of the point of the spear with regard to

England’s dealing with the Spanish Main,” Talty is quoted as saying.

Perhaps the boldest gambit in a career full of them was his attack on Panama City, one of the richest cities in the Spanish Main. From his base of operations in

Port

Royal, Jamaica, Morgan assembled a fleet of 36 ships, 1,846 men, and almost 250 cannons. Their plan was to take Fort San Lorenzo, sail up the Chagres River, and traverse the Camino de Cruces to the

city - and then loot and pillage it. In January 1671, an advance party of three ships and 470 men arrived at the mouth of the Chagres, anchored nearby, and canoed and hiked in to attack the well-armed fort from the rear. For two days the Spanish soldiers fought hard, but the

pirates prevailed. The rest of the fleet soon arrived. Perhaps it was an excess of enthusiasm, perhaps a navigational error, but upon arrival, five of Morgan’s ships, including his flagship, wrecked violently on Lajas Reef, just below the newly taken fort. “While he’s a brilliant military strategist with a serious stroke of luck, Morgan was not perhaps the best navigator,” says Hanselmann. They hit the reef so hard that the ships shattered, and 10 men and the fleet’s only woman (a “bruja,” or witch, Morgan kept on staff) drowned.

Undeterred, the rest of the ships avoided the reef and made it to the river. News of their arrival had reached the city, where Morgan was known as “El Diablo.” Resistance along the way was minimal. “They feared him so much, they sort of melted away,” says Talty. But the fleeing populace took supplies and most of the city’s riches with them. The privateers looted and tortured, but came away with much less plunder than they had hoped. Spanish accounts claim that Morgan’s men then burned the city to the ground, though widespread evidence for this inferno has not been found in Panama Viejo, the ruins of the original Panama City.

Afterward, the city was rebuilt in a more defensible position, but Morgan’s fleet had revealed that

Spain - overstretched and debt-ridden - had at that point only a tenuous grip on the New World. “I think Morgan’s attack on Panama really begins to illustrate that rot, that their defenses were just honeycombs,” says Talty. It was, perhaps, the beginning of the end for the Spanish Main.

“Panama was pretty disappointing; it turned out to be much more important geopolitically than it was financially,” says Talty. Two months before the attack, England had signed a treaty with Spain in which England agreed to suppress piracy in the Caribbean. Though Morgan’s sacking came within the treaty’s eight-month grace period, it still proved politically inconvenient. Morgan was arrested and called back to England, but it was likely for show. He was knighted and, in 1676, was sent back to the

Caribbean, this time as part of the

establishment - lieutenant governor of Jamaica. He died in 1688, happy and drunk, on a 400,000-acre sugar plantation.

There are two “Old Panamas” in Panama City: Casco Viejo, the historic district where the town was rebuilt after Morgan’s attack, and Panama Viejo, the ruins of the original. Next to Panama Viejo is the museum of Patronato Panamá Viejo, which includes the conservation lab that is handling the cannons retrieved by Hanselmann and his colleagues. The six cannons rest in

water baths in the facility, where researchers hope to learn how they got to be on Lajas Reef. Ruth Brown, formerly of the Royal Armouries in the Tower of London, has several decades of experience studying cannons, and was called on to help identify the Lajas Reef finds. The first telling detail is the size of the guns. They are short, of small caliber. The four smallest are likely to have been deck guns. Pirates and privateers either seized their cannons or purchased them on the secondary market, often resulting in a diverse collection of sizes and makes. No two among them are the same.

Two have been treated, using saws and wire brushes, to remove the stony concretion around them. Brown, who examined photographs of the cannons, has looked at their shapes, designs, ring patterns, settings, build quality, and markings. The cannons carry weight marks in English units and a “P” indicating they had been “proofed.” “That means someone’s tried it out and it hasn’t blown up in their face,” says Brown. After the 1690s, makers’ marks were cast on cannon trunnions, but these cannons lack such marks, strongly suggesting they were made earlier. The absence of broad arrows means they were not military cannons, but were used by English merchants or pirates. “Everything is consistent with what you would expect [for a Morgan ship], but there’s no killer blow either way,” says Brown. She hopes that one of the others might hold a maker’s mark that will help pin the age of the cannons down more securely. The evidence so far, and the fact that no other ships from the period are known to have wrecked on the reef, help make a strong circumstantial case that Hanselmann’s team has indeed found the only known archaeological remains of Morgan’s Panamanian raid.

There are tantalizing hints that more lies buried near the reef. Damage on the reef suggests that much has already been removed. Online auctions have offered items claimed to have come from Lajas Reef, including a hand grenade, a breechblock, and a 17-inch pewter plate marked “Port

Royal” - perhaps direct evidence of Morgan’s presence. Also, a report from a treasure hunter in the 1970s stated that there were once more than 140 cannons on the reef, along with 22 anchors, thousands of cannonballs, buckles, muskets, and even an inscribed pocket watch. When the same man returned years later, most of the material was gone. But some may remain, buried under the sand. “We have some really promising clusters of anomalies that are just to the west of the reef,” says Hanselmann. “Given prevailing winds, river current, and ocean current, that would be a good [resting] place for ships that sank after having hit the reef and then being pushed off.”

After announcing the retrieval of the cannons in a press conference in 2010, Hanselmann’s team was approached by representatives of the Captain Morgan Rum Brand. Sensing an opportunity for marketing and media, they asked how they could help. “Well, write us a check,” Hanselmann told them. So they

did - supporting the last two field seasons. The 2011 expedition was the team’s first full field season of magnetometer surveys and circle searches, followed by another in 2012. They have already found one shipwreck, perhaps a Spanish merchant vessel, that is helping provide some of the socioeconomic context into which Morgan’s fleet sailed in 1671.

It is thought - with good reason - that there are many more wrecks to be found among the

magnetic anomalies beyond Lajas Reef. Twenty ships are known to have gone down in the immediate area, with more than 12 from the

Gold Rush period alone, including Lafayette, a steamer that burned with Gold Rush passengers aboard in 1851. There are possibly many more. The search for Morgan’s ships is just one piece of what will be a cluster of projects looking at different wrecks, different time periods, and related sites on land, including the fort and the now-vanished Gold Rush boomtown known as Yankee Chagres. “Through this overarching study, people can now pick certain aspects and begin to work on them,” says Delgado. “It’s a tremendous laboratory for ongoing archaeological work.

In this work of fiction, John

Storm is aware of the find of the Satisfaction, and the fact that Henry

Morgan operated out of Jamaica's Port Royal, using Providence Island as a

convenient springboard, from whence to launch his attacks on the Spanish

held mainlands.

PIRATES

LINKS

Bellamy,

Samuel - Black

Sam (Captain)

Blackbeard

- English Teach and the Queen

Anne's Revenge

Bonny,

Anne - Pirate

Drake,

Sir Francis - Privateer

Edward

England - Irish pirate, Edward Seegar

Golden

Age of Piracy

Hawkins,

John - Privateer

Hornigold,

Benjamin - Privateer Captain

Jolly

Roger - Pirate flag

Kidd,

William - Captain Kidd, privateer/pirate

Morgan,

Henry - Privateer, Sir

Henry Governor of Jamaica

Pirates

- Piracy

and Privateers

Pirates

of the Caribbean, Disney's film

Port

Royal -

Rackham,

Jack - Calico Jack

Raleigh,

Sir Walter - Privateers

Read,

Mary - Pirate

Robert,

Bartholomew - Black

Bart, pirate

Robert

Louis Stevenson

Samuel

Bellamy - Black Sam, the pirate

Skull

and Crossbones - Pirate flag

Tortuga

-

Treasure

- Maps

to buried gold and jewels - Island

Vane,

Charles - Pirate captain

Captain

Morgan died in 1688, taking with him the secret location of his buried

treasure. Except that Edward Teach also knew of Skeleton Island, but unlike

Sir Henry, he never recorded nor shared that information.

Blackbeard

was one of the most feared pirate captains operating in the Caribbean

Sea.

When he resumed pirating, the British made it their business to capture him

as an example to other would be renegades.

|